This personal letter reflects on a spiritual journey through Korean Buddhist imagery, the figure of Jijang Bosal, and the moral implications of the fractal as presence. It links Eastern and Western thought (Buddha, Jung, Sartre) and proposes a compassionate model of reality. A meditative offering, not a doctrine.

So this is what Jijang’s Fractal and I ask of you: Stay — with what is not resolved, not named, not escaped. Let this presence shape how you listen, how you walk, how you witness. Because what is truly witnessed, no longer needs to be denied. And what is no longer denied, begins to heal — in you, in others, in the world.

Hugo J. Smal

15 juli 2025

To the Sangha — near and far, past and present,

This is not a canonical sūtra.

But it was written as one might write a sūtra:

in silence, in vow, and in offering.

Writing about Bogwangsa turned out to be more than a journey through Buddhist icons. It became an inner path toward insight. A ritual. A practice of silence and reflection. A prolonged meditation on what I now call the Jijang Fractal. It urged me to stop. To be still. To listen.

“With my head directed toward Buddhahood, and my heart committed to the liberation of others…”

This is the vow I intend to live by in the two decades I may still be given. But to walk such a path requires realignment — of mind, of body, of spirit. That is why I turn to Akasagarbha (허공장보살, Heogongjang Bosal), often referred to as Jijang’s twin brother. His name means “Womb of Space” or “Essence of the Ether.” He is the protector of wisdom, creativity, and inner expansion — the vast silence in which compassion becomes possible.

Heogongjang Bosal opens the kosmos in which the Jijang Fractal — and my vow — may unfold. That kosmos includes my own body and mind. In recognition of this, I admitted myself for a short stay in Zuyderland Hospital to have my medications recalibrated. Diabetes type 2 and high blood pressure forced me to radically change my diet: no sugar, no salt, no fat. Fortunately, Korean cuisine has always taught me that pleasure does not depend on these ingredients. There are other ways.

I am sixty-seven years old now. I want to give myself twenty more years — to be with the Buddha, and to help others. Concretely, that means focusing on the children and grandchildren of my beloved Mickey Paulssen. The world in which they must build their lives is one of crisis and fracture — ecological, social, spiritual. A world that often feels like a hell, pierced only now and then by slivers of sunlight. I ask Heogongjang Bosal to help shape that field. And I invite Jijang to guide me in carrying his Fractal into the world.

A Poetic Beginning

I wrote the following poem when I was about twenty. My literature teacher, Paula Gomes, once remarked that by writing it, I had already found her — the voice, the ground, perhaps even myself.

But I disagreed. To me, the poem didn’t offer resolution. It pointed. It called. It gave not an answer, but a task.

You search for words, for years

Of simply growing older

Always vague and afraid

Yes — back then, I was indeed searching for words. Words that might help me understand the world, and plant my feet a little more firmly on the earth. Jung, Sartre, de Beauvoir: these were the thinkers I turned to for inspiration. I also immersed myself in Eastern philosophy, but could not truly grasp it. My mind — my rational understanding — was not yet capable of feeling it. Looking back, I now realize how often I must have needed Heogongjang Bosal to help me lay a deeper, inner path. Perhaps now, with the Jijang Fractal, I have finally found the words.

Three Voices: Sartre, Jung and the Buddha

Interpretation of the Poem by Three Voices

| Line | Sartre | Jung | Buddha |

|---|---|---|---|

| You search for words | Existence precedes essence — freedom requires choice. | Call of the Self — the process of individuation begins. | Clinging to concepts — tanha obscures insight. |

| For years of simply growing older | Absurdity of time — facticity without higher meaning. | The ego ages, the Wise Old Man archetype ripens. | Anicca (impermanence), dukkha (suffering). |

| Always vague and afraid | Ontological angst — fear before radical freedom. | Encounter with the Shadow — unconscious material rises. | Avidya — ignorance just before awakening. |

Jean Paul Sartre would probably read the poem as follows:

“You search for words”

For Sartre, there is no pre-given essence. Existence precedes essence. You are — and only through choice do you define yourself. To search for words is to face the responsibility of becoming, without blueprint or certainty.

“For years of simply growing older”

Time is absurd. Sartre would see this as the human being caught in facticity — you age, your body changes, and you must relate to this without any higher justification. You become, but to what end?

“Always vague and afraid”

This fear (angoisse) is existential: it arises when one confronts the abyss of radical freedom. Every choice is both liberating and paralyzing. “Vague and afraid” is not weakness — it is authenticity, if you dare to move through it.

Sartre would read the poem as an expression of the human being in rebellious freedom — condemned to be free, in a world that offers no meaning except what you create.

Carl Gustaf Jung might interpret the poem differently:

Carl Gustaf Jung might interpret the poem differently:

“You search for words”

This speaks to the archetype of the Self — the center of psychic totality, the goal of individuation. “Becoming” is the process by which one gradually grows into oneself, as an acorn becomes an oak. For Jung, it is an unfolding already seeded within you.

“For years of simply growing older”

Time here is lived by the ego — the personality navigating the world. Aging brings not only decay, but ripening. The archetype of the wise old man becomes present — the one who knows that to age is to die and to deepen.

“Always vague and afraid”

Here appears the Shadow: the parts of ourselves that we cannot name, that evade us, yet influence us deeply. Vague is the unknown unconscious. Fear is the ego’s response when nearing its edge.

Jung would see the poem as the voice of a young ego sensing the call of the Self, but not yet able to hear it clearly — caught between light and shadow, time and destiny.

The Gautama Buddha would likely say:

The Gautama Buddha would likely say:

“You search for words”

This is the human tendency to cling to concepts, categories, and language — a form of tanha (craving). The Buddha might remind us that insight arises not from speech, but from silence and direct experience. Words can become an obstacle when we mistake them for truth. They are a form of dukkha — the hunger for meaning in a world that is ultimately formless.

“For years of simply growing older”

This line recalls the three marks of existence:

– Anicca (impermanence)

– Dukkha (unsatisfactoriness)

– Anatta (non-self)

Aging reveals suffering and impermanence. It was this insight — seeing the old man, the sick, the dead — that launched Siddhartha’s path.

“Always vague and afraid”

These are symptoms of avidya — ignorance of the true nature of reality. For the Buddha, fear is not sin; it is the stage before wisdom (prajñā). Fear is the inner resistance to letting go of “I.”

He might see my poem as a reflection of suffering born from ego-clinging — a natural condition before awakening. The way forward lies not in more words, but in unfolding. In loosening. In seeing.

Of course, none of them ever read this poem. Their interpretations are, at best, imagined. And yet: where Sartre condemns us to freedom, Jung maps a deeper psyche, and the Buddha offers the path of cessation — I now sense how these three once-parallel voices begin to converge.

Nearly fifty years later, while trying to open the gates of Bogwangsa with my words, a path revealed itself — one I had long sensed, but never seen clearly. In retrospect, I see how these thinkers shaped me. This constellation of ideas is what I now share with you.

Jijang as Bridge Between Three Traditions

Jijang as Bridge Between Three Traditions

- Sartre: Freedom, radical responsibility, no essence — Jijang honors freedom but redirects it toward presence.

- Jung: Shadow, Self, individuation — Jijang appears when the ego dissolves and integration begins.

- Buddha: Emptiness, interdependence, compassion — Jijang embodies ∞ in relational suffering.

Jijang does not choose between these three voices —

He absorbs, connects, and dwells at the intersection.

His Fractal includes them all.

The Discovery of Jijang

Years ago, during a visit to Insadong — the famous artists’ district in Seoul — I discovered a small copper statue in a cluttered cabinet against a wall. It was Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Mahasattva.

Of course, I had never heard of him. But after some research, I learned that this bodhisattva descends into the hell realms that people pass through on the path to awakening. In Korea, he is known as Jijang Bosal. He goes down not to judge — but to help. His vow speaks to the vastness of his compassion:

The Four Great Vows

Sentient beings are without end — I vow to liberate them all.

Suffering is infinite — I vow to understand it fully.

The Dharma has countless forms — I vow to learn them all.

The path of the Buddha is unsurpassed — I vow to realize it completely.

The Four Vows Interpreted Through the Fractal

- 1. Sentient beings are without end → f∞(v) includes all — no one is separate, no suffering isolated.

- 2. Suffering is infinite → Compassion repeats across time — fⁿ(w) is shared and carried.

- 3. The Dharma has countless forms → The network V reflects infinite expressions of awakening.

- 4. The Buddha’s path is unsurpassed → Each iteration moves toward integration — ∞ as practice.

Through the Fractal, the Vows are not ideals above us —

they are movements within us, unfolding endlessly.

To be awakened is to see through the illusion —

the illusion of distance, of hierarchy, of otherness.

The icons in the temples are not distant figures,

but reflections of the possible.

They do not ask for worship,

but for recognition.

These are not gods,

but inner forms —

embodied insights that remind us

of who we can become at our deepest.

Jijang is not a savior outside of me,

but a personification of an inner power:

the willingness to descend into suffering,

into darkness —

and remain there until light returns.

Until light shows itself in the other.

And in me.

Jijang as Inner Guide

Gradually, I began to realize: Jijang, this bodhisattva who enters the deepest shadows, was not just a statue. He was an invitation. An inner form that appears when the ego loses its grip — when we no longer strive upward, but dare to stay where it hurts.

In this, I recognized what Jung called the encounter with the Shadow: those parts of ourselves we have hidden or denied for years, until they return, not as enemies, but as guides.

Jijang is such a guide.

Born from darkness,

Not to banish it,

But to inhabit it — with compassion.

A figure of the Self,

Not one who ascends,

But one who descends.

Jung would have seen Jijang as an archetype — an image emerging from the collective unconscious, not meant to be worshipped, but integrated. And perhaps it is precisely there — in surrender to what is, to what Jung calls the Self and Buddhists call suchness — that emptiness no longer feels threatening. It simply is.

And you are allowed to be in it.

Jijang’s Fractal within Indra’s Net

Indra’s Net — a concept from ancient Indian cosmology — describes the universe as an endless web of connections, where each node reflects all others. Nothing exists in isolation; every point carries the imprint of the whole.

Indra’s Net — a concept from ancient Indian cosmology — describes the universe as an endless web of connections, where each node reflects all others. Nothing exists in isolation; every point carries the imprint of the whole.

Jijang’s Fractal takes this one step further. It suggests not just reflection, but transformation:

- Each node w emits influence — over time: fⁿ(w)

- Each node v receives the sum of those influences: f∞(v)

- The process never ends — karma becomes iteration, not fate

This is Indra’s Net as a living, moral system — dynamic, infinite, and tender with memory.

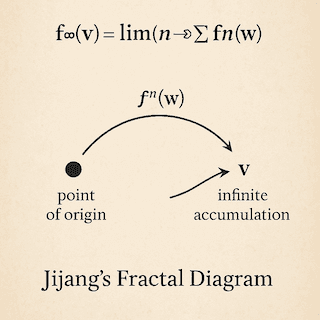

The Emergence of the Fractal

And then the fractal appeared:

f∞(v) = lim(n→∞) Ʃ(w∈V) fⁿ(w)

This diagram illustrates how Jijang’s Fractal works:

w is a point of origin — a being who makes a choice.

fⁿ(w) is that influence repeated over time.

v is a being who receives those influences.

f∞(v) is the infinite accumulation — not as fate, but as potential.

The model shows karma not as punishment, but as pattern — a dynamic field of memory, influence and presence.

And the stories I had begun writing about Bogwangsa. What started as a stray thought, a scrap of dream, became a formula. And what looked like a formula turned out to be a bridge — between East and West. Between self and other. Between thought and silence.

It started with a simple question: what if the mind is not only shaped by what I choose, but also by what others have chosen — and continue to choose? What if memory, pain, compassion, and forgiveness are not isolated events, but repeated patterns? What if that repetition — like in a fractal — does not flatten meaning, but deepens it?

That’s how Jijang’s Fractal was born. A formula in which every choice made by every being leaves a trace. Something that returns. Something that accumulates — infinitely.

How Jijang’s Fractal Operates

- A being (w) makes a choice — an action, a word, a silence.

- That choice reverberates over time: fⁿ(w).

- Other beings (v) receive these accumulated influences.

- Jijang remains present in the field of these influences — not to judge, but to accompany.

- Over infinite iterations, f∞(v) emerges — not as fixed fate, but as potential for insight, compassion, awakening.

This is karma as pattern — not punishment.

This is Jijang’s work: staying where memory accumulates, until a being is ready to see clearly.

But this fractal is not a prison. The symbol f∞(v) contains ∞ — infinity. And in my experience, in all I saw, thought, wrote and withheld about Jijang Bosal, it became clear: this infinity is not abstract. It is a presence. A person. It is what Jijang is.

Jijang’s Fractal as Bridge Between Hinayana and Mahayana

Jijang’s Fractal shows that the path of individual liberation (Hinayana) and the path of universal compassion (Mahayana) are not separate roads — they meet, and even strengthen one another.

In Hinayana, the individual is central:

v is the point of consciousness, the person responsible for their own choices.

Here, freedom is personal — and liberation is pursued through insight, discipline, and moral clarity.

In Mahayana, the network is central:

All beings are interconnected through causes, memories, and intentions.

Here, freedom is relational — and liberation arises from compassion for all sentient life.

The Fractal unites both:

f∞(v) = lim(n→∞) Ʃ(w∈V) fⁿ(w)

The individual v is not awakened in isolation, but through the influence of the network.

And the network is not just abstract kindness, but the sum of real, repeated choices — including your own.

Jijang’s Fractal becomes a living crossroads:

– of personal responsibility and collective influence,

– of moral action and formless emptiness,

– of Hinayana and Mahayana.

Not as compromise — but as the very pivot of the Dharma wheel.

Bohyeon Bosal: The One Who Opens the Field

But as always: Jijang does not appear alone.

Before he descends,

Before he settles into the depth,

Before he unfolds his ∞ across the field of suffering —

There must be space.

Not the space of stone,

But the space of intention.

A space without judgment.

A space that says: yes, this too may hurt.

That space is opened by another: Heogongjang Bosal.

He is no preacher.

He does not hover above suffering.

He makes no promises he cannot carry.

He embodies the promise —

the action, the presence, the embodiment of compassion.

If Jijang is the one who dwells in Jiok —

not as a distant hell, but as the lived reality of suffering,

of clinging — as the Buddha taught, shadow — as Jung revealed,

and disconnection — as Sartre exposed.

Then Bohyeon Bosal is the one who builds the temple without walls.

He opens the field.

He says:

Let this be the place where Jijang remains.

Let this be the place where nothing is hidden.

Let this be the place where truth may repeat itself —

without becoming shame.

Bohyeon Bosal is the stillness before Jijang arrives.

The breath before the first tear.

The moral space in which Jijang does not drown —

but works.

And so I understand now:

Jijang is ∞,

But Bohyeon Bosal is the 0

In which infinity may appear.

Emptiness Before Form

In Korean spirituality — as in its architecture — creating a space before the form is not incidental. It is essential. The field must be opened before the structure may arise.

Because Jijang is the one who remains. In Jiok. At the crossroads. In the hell realms — not as punishment, but as promise. He is the limit. He is ∞. He is the hand that keeps touching everything — without holding on to anything.

Then I began to see: this fractal is not just a mathematical model. It is a moral space. A spiritual map. A bridge between Sartre and the Buddha. For in the West, we believe in choice. In freedom. In responsibility. While in the East, the focus lies on emptiness, interdependence, and the dissolution of self.

But in Jijang’s Fractal, all comes together. Here, freedom is not detachment — but connection. Emptiness is not disappearance — but passage. And Jijang, as ∞, stands precisely at the crossroads. In the silence between ‘I’ and ‘not-I.’ Between karma and liberation. Between story and stillness.

A Return to Bogwangsa

So I began to look back at my time in Bogwangsa. Not as memory — but as repetition. What returned? Which choice, which word, which look from another kept echoing in me? Which Jijang stood still — and watched me without judgment?

That’s the hard part. Not because it is complex. But because it is intimate. Because it is real. And because it requires me not only to look at the light — but also at the crossroads within myself. The place where Jijang’s hand rests. The place where the story begins again.

When the Image Breaks

Just as Wonhyo drank from foul water in the cave — mistaking it for something pure until daylight revealed its true nature — his awakening came not through doctrine, but through the body. Through shock. Through immediacy. He saw that it was not the water that changed, but his perception of it. And in that moment, something irreversible shifted.

Moments like these still happen — not within the structures of temples or texts, but in the messiness of real life. They arrive uninvited, without explanation, and often without language.

I once witnessed something similar, though quieter. Novi was barely one year old. In our little garden stood a small stone Buddha. One day, with the open curiosity only a child that age can have, she reached out and struck it. Not in anger — there was no malice, only movement. The statue fell. The head broke off.

There was no lesson. No explanation. Only stillness.

And yet that moment stayed with me.

Not because of the broken stone, but because of what it revealed in me.

What was it I had placed in that garden?

What image was I clinging to?

What part of me was decapitated when the Buddha fell?

Sometimes the world doesn’t whisper its teachings.

Sometimes, a child’s hand becomes the finger pointing at the moon.

It is in such small ruptures that the Dharma sometimes reveals itself.

Wonhyo – The Laugh and the Bridge

And then there is Wonhyo.

He, who drank water from a skull — and laughed.

Because what first seemed impure turned sacred the moment perception shifted.

That moment became his awakening:

The realization that truth is not bound to form — but to experience.

Wonhyo, the monk who stopped traveling,

Because he understood that the journey took place within.

The philosopher who worked to bring together the many Buddhist schools of Korea —

Not to oppose them, but to place them side by side.

He did not wish to absolutize the sutras,

But to integrate them.

He became a bridge.

And that is what I hope to become.

Not to explain Korean Buddhism,

But to make it touchable.

Not to convert the West,

But to offer it a hook —

A pattern, a fractal,

On which thoughts, feelings, stories, and experiences may rest.

Jijang’s Fractal is my way of saying: You are not alone.

Not in your choices,

Not in your suffering,

Not in your freedom.

Just as with Wonhyo, I believe that truth is not possession —

But movement.

Not a system —

But a current.

Not an endpoint —

But a crossroads.

You decide what you see.

You decide what you carry.

You decide what you pass on.

And that is freedom.

And that is responsibility.

And that is the spirit of Jijang.

And that is my mission.

If this speaks to you —

If you recognize yourself in this field of influences —

Know this: the door is open.

Jijang’s Fractal is not mine — it is ours.

And it lives in anyone who dares to stay where it is dark,

Until the light reveals itself.

“With my head directed toward Buddhahood, and my heart committed to the liberation of others…”

In Closing

This letter is written in trust — not in persuasion, but in resonance.

To those who recognize something of themselves in these words, I offer an invitation: not to agree, but to enter into dialogue.

Not to resolve, but to listen.

Not to be right, but to respond.

To every member of the Sangha — monastic or lay, Korean or not, spiritually rooted or still searching — I pose this question:

What is your response to these times?

If something in this work has stirred you — whether with recognition or resistance — don’t hesitate to reach out.

Not to me as a person, but to that which transcends us, and yet binds us together.

If you feel this letter may speak to others as well,

sharing it is deeply appreciated.

In presence, in vow,

Hugo J. Smal

This reflection is part of the Bogwangsa Series on Mantifang.com — written as both offering and inquiry.

Further Reading

- Learn Religions: Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva

- Wikipedia: The Self in Jungian Psychology

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Buddhist Philosophy

- Lion’s Roar: Caught in Indra’s Net

Temporary pause on koi exports — healing park in development

International koi exports are currently on hold. Meanwhile, we are laying the foundations for a nature-driven healing park in Goyang that blends koi culture, art, and quiet craftsmanship. For updates or collaboration, feel free to get in touch.

Contact Kim Young Soo

Jijang as Bridge Between Three Traditions

Jijang as Bridge Between Three Traditions