By: Hugo J. Smal

Bogwangsa: With my head directed toward Buddhahood and my heart committed to the liberation of others

For years, the statue of Shakyamuni Buddha stood beside my koi pond. Not only because it gave the garden the right atmosphere, but because I cherished those quiet late evenings — listening to the water and the koi — letting his silent gaze wash over me. It was my way of meditating, feeling compassion. Sometimes I would light a candle. Or incense.

Koi Pond Reflection and the Buddha’s Gaze

The pond had to be emptied. For Korea, for the breeders — like the passionate team at Goyang Koi — for a greater story. I let nature take over. Frogs and salamanders claimed the 30,000-liter basin. Siddhartha remained — solitary — at the edge of a small biotope.

The pond had to be emptied. For Korea, for the breeders — like the passionate team at Goyang Koi — for a greater story. I let nature take over. Frogs and salamanders claimed the 30,000-liter basin. Siddhartha remained — solitary — at the edge of a small biotope.

Now, years later, my garden is too small. No more pond, no more room for Nishikigoi. Just a few square meters. Barely enough for an inflatable kiddie pool. And, of course, a Buddha.

That’s okay. I’ve given myself two tasks: To help Mickey care for the little ones. And to write my book: Koreans and I Both tasks aim to make the world just a little more beautiful.

Liva and Novi Under the Parasol

Liva, nine years old, has already made grateful use of the kiddie pool. Under the parasol, playing with cups and plates. Making soup for us. Splashing, giggling. Shakyamuni stood nearby. Not lonely this time, but sprinkled with childlike life.

This year, four other little beings will join her. Novi — just one year old — can’t wait to play with her sister. Merih, six months, will enjoy his first splashes. Alpje (five) and Aleyna (three) may not be around as often, but they too will sit beneath the parasol, wet-haired in the sunlight.

While Novi Climbs and the Buddha Falls…

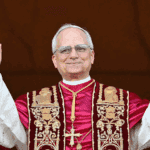

While uploading this story, something unexpected happened. A new pope was elected: Leo the Fourteenth, an Augustinian monk. His order, once home to Martin Luther. His name, once worn by emperors. And now he walks onto the world stage with a vow of humility.

His namesake, Leo the Thirteenth, steered the Church toward social justice in the late 19th century — calling for dignity, workers’ rights, and the care of the poor.

A man with his head turned toward Suchness, Just-this-ness and his heart committed to the liberation of others. I smiled. Not because I believe in omens — but because sometimes, things align. A child climbs off a couch. A Buddha loses his head. A monk becomes pope. And somewhere, in all that quiet noise, I hear Dylan sing:

“I can’t help it when I’m lucky.”

I stood there. And suddenly, an ancient image struck me. A different blow. From another time. A monk. A cave. A skull.

The Cave of Wonhyo – A Buddhist Insight

The rain fell like thoughts on stone. Heavy. Rhythmic. Silent. The monk Wonhyo, on his way to faraway China in search of true dharma, sought shelter for the night. The mountains were quiet, and an opening in the rock called to him. He stepped inside — tired, but without fear.

The darkness was total, as if he had entered the belly of the earth. There, feeling his way, he found a bowl. The water tasted pure. He drank and fell asleep. Morning arrived, and with it, light that changed everything. The bowl turned out to be a skull.

The water — stagnant rainwater, filled with leaves and death. He recoiled, his stomach churned. And then, the insight came — sudden, and clear as morning itself: What had changed between night and day? Not the experience, but the mind. His mind had first drunk clarity, then disgust — but the water had remained the same.

In that cave — no temple, no scripture, no teacher — Wonhyo awakened to the essence. Truth did not need to be found in distant lands or complicated texts. It had awakened him. He turned back. To home. To the people.To simplicity. And from that moment on, he no longer spoke of enlightenment. He lived it.

What the skull and stagnant water did for Wonhyo, Novi did for me. The icon — the image of Gautama Buddha — did not give its power as a sacred figure, but as a mirror.

A Broken Icon, a Returned Insight

With my head directed toward Buddhahood and my heart committed to the liberation of others, Novi gave something back to me — with one single blow. The timing of the lantern parade in Korea felt like more than coincidence. In the Netherlands, we don’t celebrate Buddha’s birthday. But we do celebrate Liberation Day — on May 5th. It was on that same day that I published the final chapter of the Bogwangsa story. Unplanned. Just as it needed to be.

Bogwangsa – Four Stories, One Journey

Four stories. Four moments of pausing, observing, and continuing. When I started writing about Bogwangsa, I had no plan. At best, a direction: inward. What began as a travel account of a Buddhist temple in South Korea evolved into a polyphonic reflection — of silence, loss, myth, insight, and liberation.

What I learned is not easily put into words. But I try, because every story we share might open someone else’s inner door.

In the first story, I found silence. Not as the absence of sound, but as the presence of space. The pandemic brought everything to a halt — and at the same time, something opened. Bogwangsa became not a place, but a state of being. Lost in stilness

In the first story, I found silence. Not as the absence of sound, but as the presence of space. The pandemic brought everything to a halt — and at the same time, something opened. Bogwangsa became not a place, but a state of being. Lost in stilness

![]() In the second story, I discovered the power of icons. Not as sacred objects, but as mirrors. They challenged me: What do I revere? Where do I seek protection? And what am I willing to face? Bogwangsa five Icons Bogwangsa temple, five icons

In the second story, I discovered the power of icons. Not as sacred objects, but as mirrors. They challenged me: What do I revere? Where do I seek protection? And what am I willing to face? Bogwangsa five Icons Bogwangsa temple, five icons

In the third story, I was moved by legends handed down for centuries. I learned: myths are not meant to prove truth — but to bring insight. Sometimes, a myth is the shortest route to the heart. mythical insights

In the third story, I was moved by legends handed down for centuries. I learned: myths are not meant to prove truth — but to bring insight. Sometimes, a myth is the shortest route to the heart. mythical insights

And in the fourth story, everything came together. The child, the monk, the mountain, the dream. What began as a study of something outside me, brought me back within. And there, between the lines, I may have glimpsed what some call compassion. Bogwangsa: The Dream, the Mountain, and the Fractal of Compassion

And in the fourth story, everything came together. The child, the monk, the mountain, the dream. What began as a study of something outside me, brought me back within. And there, between the lines, I may have glimpsed what some call compassion. Bogwangsa: The Dream, the Mountain, and the Fractal of Compassion

These four stories together form a small pilgrimage. Not through time, but through attention. Not toward a sacred place, but toward a sacred posture.

Just-This-Ness – What Remains

I am not a Buddhist. But with my head directed toward Buddhahood and my heart committed to the liberation of others, I’ve found something I cautiously hope to share: a way of writing that is also a way of listening. Read the stories. Let them sink in. And maybe — just maybe — you’ll meet something of yourself within them. Just as I met myself in that strike from terror baby Novi — and discovered:

I am not a Buddhist. But with my head directed toward Buddhahood and my heart committed to the liberation of others, I’ve found something I cautiously hope to share: a way of writing that is also a way of listening. Read the stories. Let them sink in. And maybe — just maybe — you’ll meet something of yourself within them. Just as I met myself in that strike from terror baby Novi — and discovered:

There is something in me that is not broken.

Not because I’m perfect — far from it.

Not because I understand — because most of the time, I don’t.

But because, beyond all I’ve been, or endured,

something remains.Still and clear.

Still and warm.

Still and real.I don’t call it God.

I don’t call it Self.

I don’t call it Soul.

I don’t need to name it.But I know: it watches with me.

And when I am very quiet,

I am it.Sometimes I think I must be mad to feel this.

Then I hear voices — inside or outside — saying:

Who do you think you are?

But I don’t think anything.

I know I’m not it.

I’m not that stillness.

But it is in me.Maybe this is what the Buddha saw when he said:

“All beings already have it.”

Maybe I don’t need to become anything.

Maybe I just need to write.

To point.

To show:Look — here something shines.

Also in you. Suchness, Just-this-ness

Curious what ‘suchness’ really means?

I invite you to follow me Hugo J. Smal , Jijang’s fractal or Spiritual East Asia