Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897)

joseon dynasty (1392–1897) was korea’s longest-ruling confucian state, shaping society, culture, economy, and governance for more than five centuries.

joseon dynasty — key highlights

- 1392 — General Yi Seong-gye establishes the joseon dynasty, adopting confucian governance as state ideology.

- 1443–1446 — King Sejong oversees the creation of Hangul, korea’s unique alphabet, revolutionizing literacy.

- 1592–1598 — Imjin Wars: japan invades korea; Admiral Yi Sun-sin defends with his famous turtle ships.

- 17th century — Confucian philosophy (Neo-Confucianism) dominates society, education, and politics.

- 18th century — Cultural flourishing with advances in painting, ceramics, printing, and architecture.

- Late 19th century — Reforms and external pressures weaken joseon, paving the way for the Korean Empire in 1897.

Culture, science, and governance

The joseon dynasty fostered a rigid but enduring confucian social structure. Scholars of the yangban class preserved order, while commoners lived under strict hierarchy. Within this framework, korea achieved major cultural milestones.

Scientific advances included rain gauges, celestial globes, detailed maps, and medical texts. King Sejong’s reign became legendary for its patronage of innovation, particularly the invention of Hangul, which transformed literacy and cultural identity. Art thrived as painters developed true-view landscapes, ceramics evolved with refined white porcelain, and printing spread classical as well as practical knowledge.

Philosophy was dominated by neo-confucian korea, guiding governance and education. Debates on ethics, human nature, and governance shaped institutions that lasted centuries. This system emphasized loyalty, filial piety, and scholarly meritocracy, though it also limited social mobility.

Society and international relations

While the joseon dynasty history is marked by confucian ideals, society also experienced hardship: slavery persisted, women’s rights declined compared to earlier eras, and peasant uprisings occurred. Yet everyday life was also shaped by family rituals, seasonal festivals, markets, and farming communities that tied people closely to the land.

Agriculture formed the backbone of the economy. Rice paddies, irrigation systems, and land reforms sustained the population, while taxes were collected in grain and cloth. Markets expanded in cities such as Hanyang (modern Seoul), and artisans specialized in pottery, metalwork, and paper production. Despite restrictions on commerce, a merchant class slowly gained influence, paving the way for later modernization.

Religion and belief systems coexisted. Buddhism, though suppressed politically, remained influential among commoners. Shamanistic practices and ancestral rites continued, blending with official confucian rituals. Christianity arrived in the late 18th century, sparking both persecution and intellectual debate that influenced reform movements.

Foreign invasions tested resilience. The Imjin Wars devastated korea, yet Admiral Yi Sun-sin’s victories at sea remain symbols of resistance. In later centuries, isolationist policies earned the nickname “hermit kingdom,” but contact with ming and qing china continued, while limited exchanges with japan and eventually western nations reshaped diplomacy.

Legacy of the Joseon Dynasty

The legacy of the joseon dynasty endures in modern korea. Its confucian principles influenced education, family life, and social etiquette well into the 20th century. Hangul, once resisted by elites, is today a symbol of national identity and pride. Ceramics, calligraphy, and painting from the era remain treasured cultural assets, displayed in museums worldwide.

Political and social contradictions — rigid hierarchy alongside remarkable cultural creativity — continue to fascinate historians. The dynasty’s final decades, marked by reform, foreign encroachment, and eventual collapse, foreshadowed korea’s turbulent entry into the modern world.

Art, clothing, and architecture

Joseon culture expressed itself vividly in clothing, housing, and city planning. The traditional hanbok developed distinctive lines and colors that reflected social status and occasion. Commoners wore plain cotton or hemp, while the elite dressed in silk garments, often with symbolic colors such as white for purity or blue for scholarly virtue.

Architecture combined functionality with aesthetics. Wooden palaces such as Gyeongbokgung displayed sweeping tiled roofs and courtyards arranged according to geomantic principles. Villages featured hanok houses with ondol underfloor heating, an innovation that made winters more bearable and continues to inspire modern Korean design.

Painting and calligraphy thrived, with artists producing landscape scrolls that captured Korea’s mountains and rivers in naturalistic style. Court painters documented ceremonies, while folk art such as minhwa spread among the wider population, blending humor, symbolism, and religious motifs. These artistic forms provided continuity between elite culture and everyday life.

Further reading

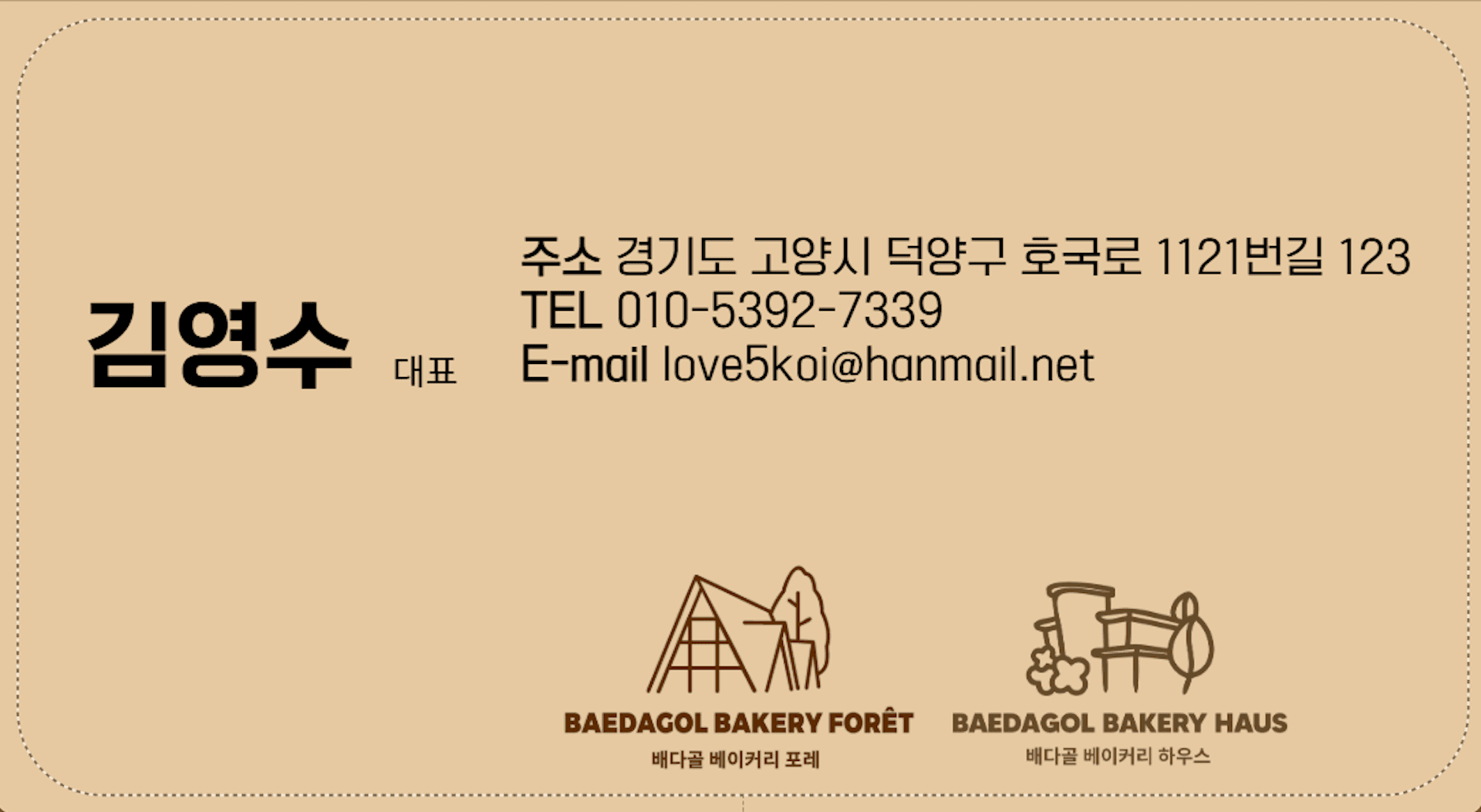

Temporary pause on koi exports — healing park in development

International koi exports are currently on hold. Meanwhile, we are laying the foundations for a nature-driven healing park in Goyang that blends koi culture, art, and quiet craftsmanship. For updates or collaboration, feel free to get in touch.

Contact Kim Young Soo