The Tale of Genji — The Broom Tree (Chapter 2)

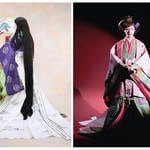

Reading Murasaki Shikibu’s Genji Monogatari, often called the world’s first novel, through the lens of the Heian period: courtly etiquette, Miyabiそして モノ・ノー・アウェア shape the world around Genji.

これ.

の中で Heian period, conversation gravitated to poetry, protocol, and prestige. Men debated rank and aesthetics; women were too often the topic rather than the speakers. Politics meant paperwork: fussy discussions and the careful choreography of status. The game of power had to be played perfectly.

In this classic Japanese novel, love and loss intertwine with the complexities of court life.

Genji’s world: art, etiquette, and feeling

Art mattered. Exchanging poems was crucial. Miyabi—courtly refinement—was law. Donald Keene noted that nothing in the West matches the role aesthetics have played in Japan since Heian; the spirit of refined sensitivity still shapes modern aesthetics. Closely related is モノ・ノー・アウェア: a readiness to be moved by people and by nature.

Genji Monogatari illustrates the delicate balance of emotions and social norms.

Heian-kyō (Kyoto): small island of rank

The world of Genji was claustrophobic. The nobility—dominated by the Fujiwara—clustered in Heian-kyō (Kyoto), perhaps a thousand people within a city of a hundred thousand. From the seventh century, members of the Hata clan—immigrants from Gaya/Silla in Korea—settled there. The capital (from 794) followed Chang’an’s grid and Feng Shui principles.

Downtown Kyoto was closed to commoners. Goods arrived at the gates; people of lesser rank remained invisible to the elite. Their island of privilege measured only four square kilometers.

Read more on Feng Shui and East Asian capitals in my story “Shikibu’s モノ・ノー・アウェア, transient beauty”:

このサイト

Genji, son of Emperor Kiritsubo and the low-ranked concubine Kiritsubo Kōi, was beloved by the Emperor and envied by rivals. To shield him from court politics, he was removed from the line of succession, given the Minamoto name, and began a career as an imperial officer—Hikaru, the “Shining One.”

Chapter 2: The Broom Tree

Genji is married to Aoi, daughter of the Minister of the Left (Sadaijin). His friend Tō no Chūjō and other officials gather at Genji’s residence. Their topic: women, rank, and the perils of choice in a strict hierarchy.

“…lying there in the lamplight, against a pillar, he looked so beautiful that one could have wished him a woman. For him, the highest of the high seemed hardly good enough.”

Who to choose? Behind curtains and screens, encounters were coded by poems and perfumes. Is this one of literature’s early hints of a homoerotic gaze? Perhaps; beauty often unsettles categories.

A personal aside: my first shock of beauty came in 1965 on a new black-and-white TV—Brian Jones with his sitar. An angel. Hikaru, shining. As with Genji, charisma reframed everything around it.

Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting within the Fujiwara, wrote men from a distance—and yet with piercing insight. Her imagination animates this courtly world.

Poems, perfume, and protocol

Marriage among nobles could involve multiple wives and concubines. Courts were strict, encounters discreet. A poem—sometimes borrowed from Chinese literature—was brushed on fine paper, scented, and sent with a flower. If a lady’s heart moved (モノ・ノー・アウェア), she replied in kind. Love could fail, too:

Near the end of the chapter: “When he learned that there was no hope… he was very hurt.”

“I who never knew what the broom tree meant now wonder… the broom tree you briefly glimpsed fades and is soon lost in view.”

Note on the image: the broom tree at Sonohara (Shinano) was said to vanish as you approached; the woman’s humble origins make her “disappear” in the eyes of rank.

Kichijōten and the limits of perfection

“…in the end, it is simply impossible to choose one woman over another… Set your heart on Kichijōten herself, and you will find her so pious and stuffy, you will be sorry!”

Kichijōten is the Buddhist form of Lakshmi—goddess of beauty and fortune—perhaps too perfect even for Genji. Politics soon enters the tale; Genji’s skill there will matter as much as love.

📖 Discover My Korean Journey

Alongside exploring the Tale of Genji, I’ve been writing about my own experiences in Korea — stories of culture, history, and everyday encounters that shaped my perspective.

Dive into 私の韓国旅行 to follow these reflections and see how East Asian traditions connect with modern life.

さらに読む

Want to explore more about Genji Monogatariその Heian period, and Japanese aesthetics? Here are trusted sources:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — The Tale of Genji overview

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art — The Tale of Genji in Art

- Nippon.com — Genji Monogatari and Japanese Literature

- British Library — Tale of Genji manuscripts

- Wikipedia — The Tale of Genji