geschreven door Hugo J. Smal

korean kitchen food; not trying is not living.

That line stayed with me after my first real Korean meal. Not because it sounds clever, but because it’s true. In Korea, eating isn’t an activity. It’s a state. A shared state in which body, attention, and relationship merge. Use Koreaans eten for type 2 diabetes!

When you sit down at a Korean table for the first time, it looks like chaos. Bowls, small plates, metal cups, bottles, rice (bap 밥), raw garlic (maneul 마늘), peppers (gochu 고추), lettuce leaves (sangchu 상추), steaming soups (guk 국), spoons and chopsticks crossing paths. It can feel like a post-war landscape. But that apparent disorder is the order. Everything is present. Nothing stands alone.

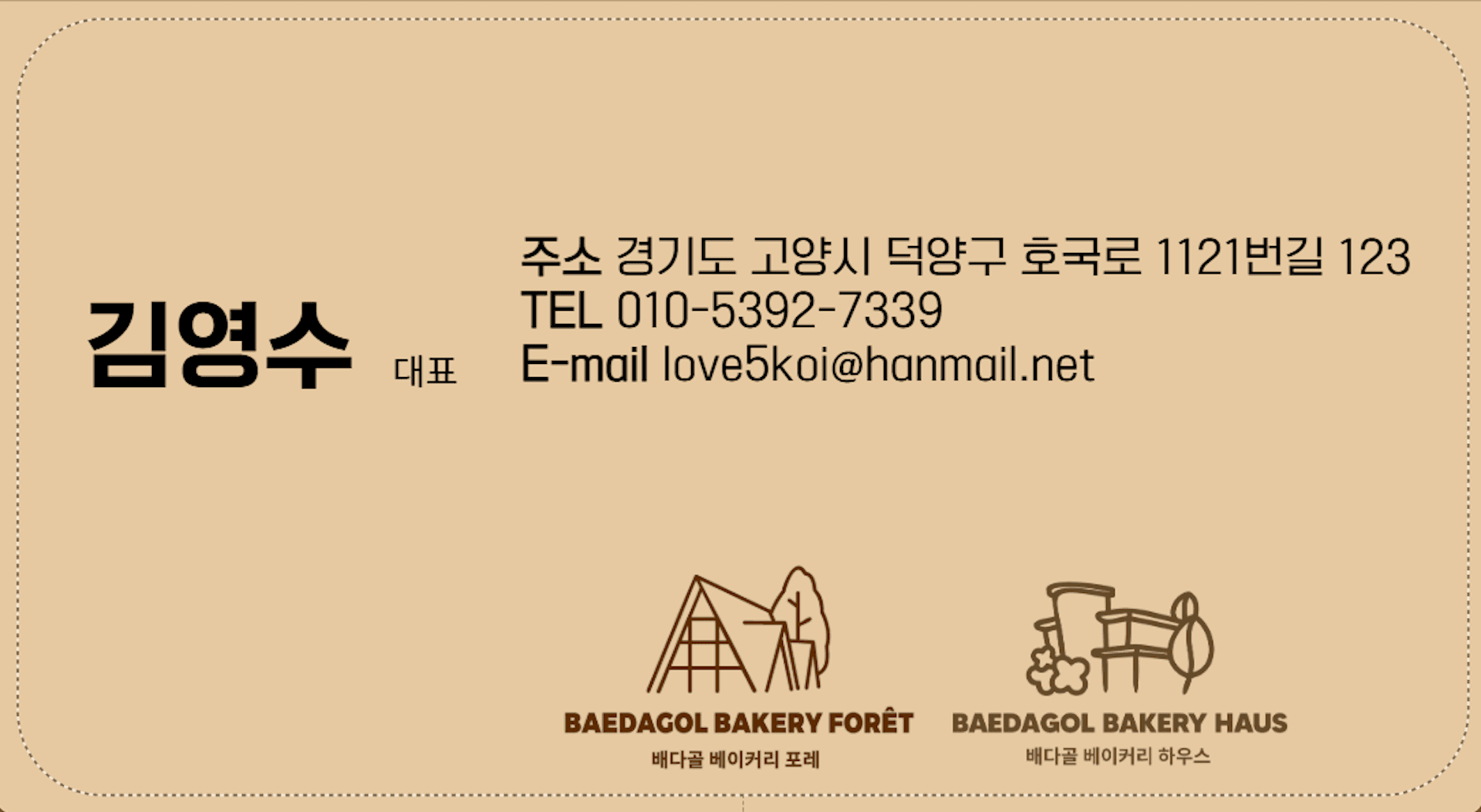

I have often eaten at tables that were simply too small for what they had to hold. And there is always that moment when Kim Young Soo stands up to pay, while two men nearby argue loudly. Not about who should pay, but about who gets to. That is Korea too. Food is relational. You don’t only feed yourself.

Fermentation — the body’s memory

If you must name one foundation of Korean cuisine, it is fermentation (balhyo 발효). Not a trend, not a health slogan, but a form of memory—time preserved in taste.

Kimchi (김치) is the most famous, but it is only one voice in a choir. Doenjang (된장), ganjang (간장), gochujang (고추장)—fermented flavors that do not shout, but remain. They began as necessity: vegetables had to survive the winter. What started as survival became culture.

In autumn—still—families make kimchi (kimjang 김장). In Goyang-si, where I often stay, you see small gardens, containers, hands that know what to do. Not out of nostalgia, but because it works.

For someone living with type 2 diabetes, fermentation is not a detail. It slows. It satisfies. It supports the gut. It softens peaks. Kimchi is not medicine, but an ally—designed not to “fix” you, but to give the body room.

Buddhist cuisine — attention as direction

But time alone is not enough. Time needs direction. In Korea, that direction was guarded for centuries by Buddhist temple cuisine, sachal eumsik (사찰음식).

In temple kitchens, cooking is not about seduction. There is no spectacle, no signature, no hurry. Cooking is part of practice (suhaeng 수행): attention, moderation, compassion. A meal is not a reward, but support.

Temple cuisine avoids meat and fish, but also the osinchae (오신채)—garlic, onions, scallions and relatives—because they are seen as stirring the inner fire. For a body already struggling with regulation, that insight feels unexpectedly current.

What remains is not deprivation but richness: grains, legumes, mushrooms (beoseot 버섯), wild mountain greens (san-namul 산나물), roots, seaweed (gim 김, miyeok 미역). Everything is used. Waste is minimal—not as an idea, but as instinct.

Cooking is slow. Not romantic, but necessary. Hurry and attention do not coexist easily. And when you cook attentively, you eat differently. You chew differently. You stop earlier.

Baedagol — learning through closeness

In temples, recipes are rarely written down. They are passed on through closeness—by watching, joining in, repeating. That touches what Baedagol can be at its best: a place where generations meet without the urge to explain.

Older people who know when something is enough. When salt no longer adds anything. When the heat can be lowered. When hunger is no longer physical, but searching for rest. Food becomes a form of transmission—lived knowledge.

For young people—in a Korea that is growing faster, heavier, and fuller—there is a quiet lesson here. Not in what you eat, but in how. Not in cutting things out, but in choosing. Not in discipline, but in rhythm.

Rice — the daily anchor

From that attention you naturally return to rice (bap 밥). The problem is rarely rice itself, but rice without context. A Korean meal is a system of slowing down: you share, you combine, you stop when the table settles.

What I actually do at a Korean table — living with type 2 diabetes

I don’t count carbohydrates at a Korean table. I watch rhythm instead. I start with soup (guk 국), not rice. Warmth slows me down. Then vegetables—banchan (반찬), namul (나물), seaweed. Only after that do I take rice (bap 밥), and never as the center, but as support.

I eat rice in context, not in isolation. Wrapped, mixed, shared. I stop when the table settles, not when my bowl is empty. Fermented food—kimchi (김치), doenjang (된장)—is not decoration for me, but structure. It steadies my body.

I don’t avoid barbecue, but I never let meat stand alone. I eat gogi-gui (고기구이) wrapped in lettuce (sangchu 상추), with kimchi, garlic, ginger, and ssamjang (쌈장). The wrap slows the bite. The sharing slows the pace.

Most importantly: I don’t eat in a hurry. Korean food gives me permission to take time. And time, I have learned, is one of the most effective forms of care for a body that no longer regulates itself automatically.

This is not a method. It is simply how Korean food, eaten as intended, meets my body where it is.

Korean eating culture and type 2 diabetes

Always green

Anyone who sees Korean cuisine as meat-heavy is mostly looking at restaurants. At home—and traditionally—the plant-based share is enormous: vegetables, mushrooms, seeds, seaweed, herbs. Preparation is often elaborate. That is why vegetables carry the meal: fiber, bitterness, minerals—everything that helps stabilize the body.

You don’t eat less. You eat more sustaining.

Korean kitchen food for type 2 diabetes: Fire, meat, and community

Yes, Korea barbecues: gogi-gui (고기구이). Samgyeopsal (삼겹살), bulgogi (불고기), galbi (갈비). But meat is never alone. It is eaten in wraps (ssam 쌈) with kimchi and ssamjang (쌈장). Everyone participates. You turn the meat for each other. That is not service—it is community.

I fold the wrap. I eat. What follows is not a taste, but an explosion. Insadong in my mouth. You don’t merely taste Korea—you experience it.

Series, Paik Jong-won, Kim Young Soo — and the Korean way of telling food

To understand Korea today, you also look at television. Cooking shows are not just entertainment; they are vessels of memory. Competitions, street-food programs, and dramas show food as struggle, care, and identity.

And above all, there is Paik Jong-won (백종원).

Paik is not a chef who seeks admiration. He is a storyteller. In his programs, food is never isolated. Each dish carries history—war, poverty, migration, survival, comfort. He explains not only how something is cooked, but why it exists. Through food, he tells the Korean story.

Paik’s Spirit — a Netflix series in which Paik Jong-won sits at the table with guests to talk about Korean kitchen food, drink, and life, using shared meals to explore Korean culture, memory, and everyday meaning rather than competition or technique.

Watch on Netflix

In my own life in Korea, Kim Young Soo plays a remarkably similar role explaining Korean food

Like Mr. Paik, Kim Young Soo is an exceptional narrator. Time and again, he has made clear to me what something is for—why a dish exists, why it is eaten this way, why it belongs to a place or a moment. From a single grain of rice to a crab claw, he has offered me the Korean kitchen not as information, but as lived meaning.

Where Paik tells Korea through television, Kim Young Soo tells it at the table. Both share the same gift: making food understandable without reducing it, and meaningful without turning it into theory.

For someone living with type 2 diabetes, this way of telling matters. It shows that health does not begin with restriction, but with understanding. Not with fear, but with context.

Korean food for type 2 diabetes as daily care

In Korea, you don’t pour your own drink. It’s impolite. You watch each other. A glass (jan 잔) is empty—you fill it. Soju (소주), beer (maekju 맥주), tea (cha 차). Drinking is care.

I once pressed a button at the table. A bell rang. And then I heard the sound I love most in Korea. The waitress said, together with the others, “deh!” We heard you. We’re coming.

Korean kitchen: Seasons, fish, and waiting

Fish markets are rhythm. You choose what is alive. You negotiate. You wait. And you wait a bit more, because fish is popular. Seasonal eating (jesik 제철) is not a trend—it is normal.

Perhaps that is the greatest lesson for diabetes: eat what is there, when it is there.

Eating Korean kitchen food as resistance to illness

I am not a cook. I am someone living with type 2 diabetes who learned in Korea that eating does not have to be punishment. Not a diet. Not a spreadsheet. But attention, structure, and sharing.

Korean cuisine restores balance: time, fermentation, community, attention.

That is why this story belongs here—under Korea op je bucketlist—connected to Baedagol and the Korean Kitchen.

Eat. Share. Slow down.

Because in Korea, it still holds: food not trying is not living.

Q&A

Is Korean food suitable for someone living with type 2 diabetes?

It can be, especially when eaten in the Korean way: rice in context, plenty of vegetables and soups, and fermented foods like kimchi and doenjang. The strength is the meal rhythm—sharing, slowing down, and balance—rather than strict avoidance.

Why is fermentation so central in Korean kitchen?

Fermentation (balhyo 발효) is a cultural foundation: time preserved as taste. Kimchi and the jang family—doenjang, ganjang, gochujang—shape Korean flavor and meal structure, and often support satiety and steadiness.

What is Korean Buddhist temple cuisine (sachal eumsik)?

Sachal eumsik (사찰음식) is Korean temple cuisine: cooking as practice—attention, moderation, and compassion. It avoids meat and fish, and traditionally avoids pungent ingredients (osinchae 오신채). It emphasizes grains, vegetables, mushrooms, and careful, unhurried preparation.

What makes Korean barbecue different from Western dining?

Korean barbecue (gogi-gui 고기구이) is communal and built around wraps (ssam 쌈). Meat is rarely eaten alone: it is folded with lettuce, kimchi, sauces like ssamjang (쌈장), and shared pacing at the table.

Why do cooking shows matter for understanding Korean food culture?

They carry memory. Storytellers like Paik Jong-won explain not only how dishes are cooked, but why they exist—history, survival, comfort, and place. At the table, Kim Young Soo plays a similar role by translating lived meaning into everyday eating.

Verder lezen

Korean Diabetes Association (대한당뇨병학회)

Official Korean foundation providing authoritative information on diabetes, including type 2, research, prevention, and public education.

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (질병관리청)

Government public health authority of South Korea with data, policy, and national context on diabetes and lifestyle-related diseases.

Follow Korean kitchen om facebook

Tijdelijke stop op koi-export - genezingspark in ontwikkeling

De internationale koi-export ligt momenteel stil. Ondertussen leggen we de basis voor een natuurgedreven genezingspark in Goyang dat koicultuur, kunst en stil vakmanschap mengt. Voor updates of samenwerking, neem gerust contact op.

Neem contact op met Kim Young Soo